Sometime during a mid-1990s winter in Akron, Ohio, my dad called me over to a window overlooking the back yard. One of his bird feeders, a yellow tube filled with thistle seed, was being mobbed by small, streaky brown and white birds, some with yellow edging on the wings and tail. To me, they looked like American Goldfinches, only they weren’t.

Pine Siskins, I was told. Two dozen at least. I’d never heard of them. I wasn’t a birder and had only a cursory knowledge of backyard birds, the kind of awareness that comes growing up in a house where the feeders are always full and the yard teeming with birds and birdsong. When it came to Pine Siskins, the casual bird enjoyer in me appreciated the spectacle without fully understanding it.

I didn’t give much thought to Pine Siskins (or any other birds) over the next ten years or so, but I also never forgot that sighting. In the meantime, I married my wife Alex in 2000, and we hopped around on various adventures (two years each in New York, Colorado, and France), until our peregrinations came to a halt in 2008 when she enrolled at Purdue University as a PhD student. Suddenly we found ourselves grounded for at least half a decade in West Lafayette, Indiana. Apartment life had suited us up to then, but now we were ready for a little more space. After all, we were in our 30s, and it was getting time to start thinking about mixing a cocktail with our DNA. As luck would have it, we found the perfect domicile to call home—the Pink House.

The three-bedroom, two bathroom Pink House was a cozy refuge during Alex’s stressful (and successful) PhD run. It also happened that our first house and first yard came pre-equipped with our first bird feeder. (And, as an unwitting housewarming gift from the previous occupant, a clothes dryer preloaded with a pile of women’s underwear, ultimately returned to their very grateful and slightly embarrassed owner). Once moved in, Dad bought us some seed, and I found a blank book to keep track of our winged visitors.

House Finch was the first entry. Northern Cardinal was number three.

That hopper-style feeder became such a squirrel magnet that I eventually replaced it with a pair of tube feeders, protected from ravening rodents by a very effective squirrel baffle. In those five years, I counted 54 birds in our yard, including a Pileated Woodpecker who was a frequent visitor when Alex was pregnant with the son we call “William.”

Those feeders led to a lot of discovery. Before them, I was unaware of the existence of White-throated and White-crowned Sparrows. Same for Red-breasted Nuthatches. I was also starting to become aware of yard birds who had little to no interest in feeders. Veery. Ovenbird. Brown Creeper. There was a world of birds out there. I wasn’t down the rabbit hole yet, but Indiana is where I first scratched the surface. Am I mixing metaphors? Ah well. Fuck it. I’m tired.

Conspicuously, year after year passed without a single Pine Siskin, let alone a couple of dozen. Since my Golden Guide described them as “Irregularly common, especially in conifers,” I chalked their absence up to a dearth of pine trees in our neighborhood and patiently waited for their possible, but not expected, arrival.

What my Beginning Birder’s Brain (BBB) didn’t know is that Pine Siskins are an irruptive species. For my readers also suffering from BBB, an irruption is when birds (typically finches) who make their home in the boreal forests of Canada venture out of their normal range during winter. Irruptions can happen when there is a spring population boom of irruptive species and/or a winter shortage of the kinds of foods these species favor, such as the seed crop that conifers produce each year. In years of crop abundance, the finches tend to stay put. In bust years, or years when populations are too large for the crop, the finches will head south in search of sustenance, much to the delight of more southern-oriented birders.

Each year, the Finch Research Network publishes its annual Winter Finch Forecast. Developed by the late Ron Pittaway and first published in 1999, the WFF looks at factors such as conifer crop yield to determine the likelihood of finches traveling south in a given year. Based on this winter’s forecast, the outlook for finch irruptions didn’t look promising. Some movement was expected, but nothing like the “superflight” of 2020 that had winter finches turning up far and wide, from Bermuda to New Mexico.

That was the winter before I started really birding, but I reaped some benefits nonetheless, as you will see. What follows is my personal relationship to each species of irruptive finch, beginning with the long-anticipated…

Pine Siskin ✅

When Alex graduated from Purdue in 2013 and was subsequently hired by Michigan State University, it was time to pack up the Pink House (underwear and all), move one state north, and settle in the city of East Lansing. This time we bought our home, though we failed to give it a cute nickname.

Up went the feeders, and a new yard list started with a Red-winged Blackbird, a bird we never recorded at the Pink House and one we owed to our Michigan home being located next to a golf course. Those 200 acres yielded many birds we never got in Indiana, including the Baltimore Orioles who were frequent visitors when Alex was pregnant with the (one) KID we call “Santiago.”

With two children, a full-time job, and a great big house to take care of, my birding was really confined to home. I kept the feeders full most of the time over the next half-dozen years, and I kept an eye on them as best I could. Finally, on November 3rd, 2020, the year of the superflight, my vigilance paid off.

The picture, taken from my second-story office window without the benefit of a zoom lens, is terrible, but several of the Pine Siskin’s field marks are there—streaky underside and back, yellow highlights on wings and tail. Even the semicircle in the cheek is evident. Less visible is the Pine Siskin’s sharply pointed beak, a less heavy organ than typically found on a finch.

Though I’ve seen Pine Siskins every year since at varying locations, that was the first and last time I’ve caught one in our yard. Rude, considering I purchased this feeder specifically with Pine Siskins in mind.

Redpoll ✅

On December third of that same year, I spotted a single tiny, streaky, grayish-brown bird with a little red cap and a red wash across its breast. Sitting in a tree in East Lansing’s Towar Wood Preserve, I knew instantly I’d found my first Redpoll, possibly the most adorable bird in all of finchdom. That new life bird made my winter, but Redpolls weren’t done with me yet. In early March, four more Redpolls, no doubt migrating back north as part of that superflight winter, deigned stop in our yard for several days. They were invited to the feeders, of course, but they seemed to prefer gather on the ground, perhaps hoping enough birds would turn up for a halfway decent game of pickup football.

Now that I’m looking at this picture again, I’m wondering if the centermost bird is the Hoary variety of Redpoll (Common, Hoary, and Lesser Redpolls were lumped into one species last year). I welcome your thoughts on that.

Purple Finch ✅

Like the Pine Siskin, Purple Finch is a bird I waited a lonnnnng time to see at our feeders. They look similar enough to the more widespread House Finch that many times I talked myself into thinking I saw one. But when you actually see a Purple Finch, you notice how different they are from House Finches. Here I invite you to enjoy another picture taken from my office window without the benefit of a zoom lens.

This male came to our feeder in October of 2020. I have not had a single Purple Finch in the yard since, though a number of them have appeared around Allegheny County this winter, including a flock of six I happened upon last week while the boys were sledding.

White-winged Crossbill ✅

Our last year in central Michigan featured a nice irruption of White-winged Crossbills. Crossbills, sporting perhaps the best bills in the ABA area, enjoy attacking pine cones in big noisy flocks. I never managed a photo of them, or even to get a satisfying look at them, but I did capture the bare tree they landed on for a two-second respite. Behold!

Red Crossbill ❌

That same winter, a number of Red Crossbills appeared in Gratiot County. When I got the notification, I hopped in the car and drove the 30 minutes north…only to miss them, I was informed by more adept (or perhaps speedier) birders, by less than five minutes. They had been circulating around the area, hitting various stands of pine trees, but I never tracked them down.

Pine Grosbeak ❌

I have no relation to the magnificent Pine Grosbeak other than we occupy the same continent. I’ve never seen one reported on eBird or any rare bird alert anywhere I’ve lived. Likewise, Pine Grosbeaks have never seen me reported on eNerd or any rare nerd alert that I’m aware of. Someday, somewhere, we will cross paths, and bird and nerd will at last be united.

Evening Grosbeak ❌

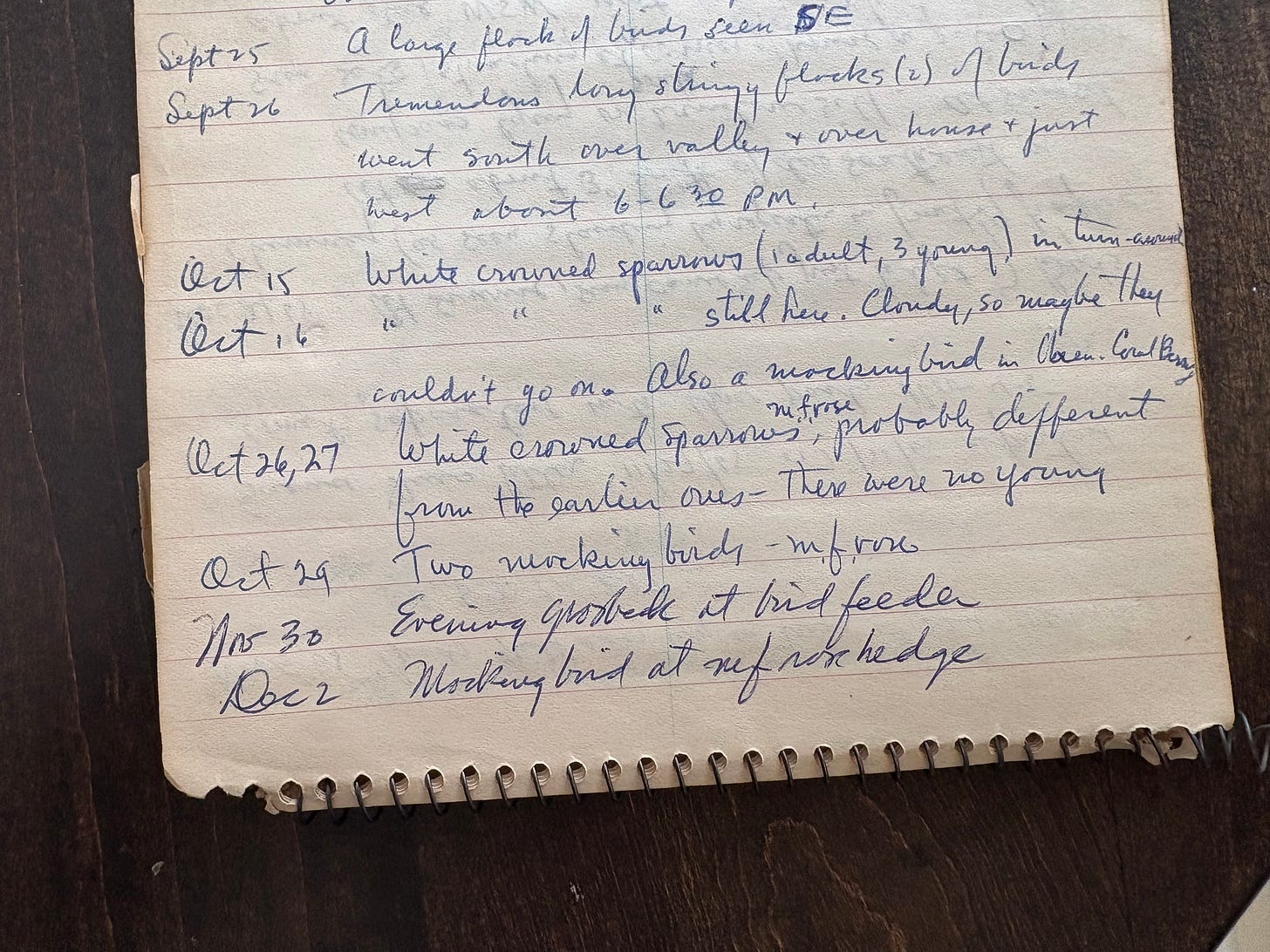

On November 30, 1966, an Evening Grosbeak visited my grandparents’ feeder in Akron.

According to subsequent entries in his journal, the bird was an almost annual winter arrival over the next decade. I imagine that was neat, though I would hardly know—in nearly twenty years of feeding birds in Indiana, Michigan, and Pennsylvania, I have yet to see one. The closest I’ve come is a single individual that turned up in our Michigan neighborhood during the 2020/21 superflight, according to eBird. That happened during the height of Covid, and I sure wasn’t going to knock on a stranger’s door about a bird while that shit was going down.

Even though this winter’s forecast didn’t predict a big irruption in 2024/25, if there’s one thing I’ve learned in the last four years of daily birding it’s that birds tend to behave how you expect them to, until they don’t. I have hope, and I’m keeping my eyes open for Evening Grosbeaks in particular. And perhaps my hope is warranted, if the WFF has anything to say about it.

“…there should be a moderate flight of Evening Grosbeaks southward this fall. Evening Grosbeaks should visit areas from the Maritime provinces south towards Pennsylvania.”

Pennsylvania, you say? Well, it so happens a job offer to my wife landed us in the Keystone State in 2022. We named our lovely home the Rookery, and it has been a birding paradise of 137 species, Pine Siskin and Purple Finch among them (though not at the feeders…yet). And sure enough, three Evening Grosbeaks were spotted at a feeder a couple of counties north of here earlier this month.

The Evening Grosbeak is perhaps my most coveted bird. It’s also a bird in trouble, having lost more than 90% of its population since the 1970. They irrupted to Allegheny County in a big way in 2020 and I’m sure they will again, but their plummeting numbers mean I should probably be a bit more proactive than I have been in years past.

Perhaps this time an open letter?

Dear Evening Grosbeaks,

Get your ass down here!

Bring friends.

Love,

Nate

All joking aside, a more than 90% loss in population in a mere 50 years is stunning, and the Evening Grosbeak is perhaps the most stark example of an overall decline in bird populations over that period of time. I hate to end a post on a downer, and so I’ll again point to the Kirtland’s Warbler and its improbable rebound as an example of what conservation-minded humans are capable of when they refuse to let a species go extinct.

Featured Photo—American Goldfinches and Pine Siskin

I was fortunate to capture a pair of American Goldfinches and a Pine Siskin side by side in this photo from last February, which illustrates just how different the two species are, in spite of the nearly identical size and shape. I enjoy the intent look on the faces of all these hungry birds, particularly the Goldfinch in the fore, watching hopelessly as a wayward morsel escapes, bound, no doubt, for the belly of some ground feeder or another.

10/10 Recommends

Since we’re discussing backyard feeders, now seems an appropriate time to talk about Amy Tan’s latest bestseller. I’ve never read one of her novels, but you can see the observant novelist’s brain in action here. The Backyard Bird Chronicles reads like a collection of bird-centered short stories, told from the vantage point of a preposterously eloquent beginning birder. Because I do almost all of my reading by ear, I’m missing out on her bird drawings. That’s a shame, but it’s easy to get caught up in the words, the raw joy and grief and frustration the author packs into her birding journey. Alternately profound and profane, this book should appeal to anyone who ever put up a feeder, only to irrevocably fall in love.

That’s all for this week. What’s your experience with irruptive finches? Have you ever seen an Evening Grosbeak? If so, know that I am sick with jealousy, but I’m also happy for you, so please share in the comments!

Until next time, bird your ass off!

nwb

This post was human-generated. All photos by Nathaniel Bowler unless otherwise noted.

once living on a lake in Quebec north of Montreal we had a variety of grosbeaks and beauties they were. Hope your sign attracts them aplenty.

So glad you have your fancy camera now. Another reason for the grosbeaks to come. They can get photographed in style!