He Wore a Raspberry Beret

Parsing a Confusing Pair of Finches

Among the myriad challenges facing a novice birder in the eastern United States today is learning to distinguish the nearly ubiquitous rosy-red House Finch from the more elusive raspberry-red Purple Finch. In fact, I’d call it something of a rite of passage for a beginning birder keen on growing their life/yard list to endlessly patrol their feeders, scrutinize every medium-sized red finch that visits, zero in on one individual that looks a bit raspberry, and loudly conclude, PURPLE FINCH!

If you’re anything like me, you ride that wave of lifer joy by quickly checking the species off in pen in your field guide. Maybe you gleefully type LIFER!!! in the comment box of your eBird checklist. After all, why not? That one really looked different. And it’s not like Purple Finch tripped the rare bird filter in eBird, the kind that demands detailed descriptions and photographic evidence, the kind that gets you a terse email from your local reviewer asking you to please explain yourself. None of that happened, and there are no prisons for misidentification. So relax. Sit back and celebrate your lifer.

But when the lifer euphoria begins to subside, ID doubt creeps in. It pecks at first, little nagging jabs that slowly intensify until, suddenly, doubt is a hawk’s bill, ripping your confidence away feather by feather. What’s more, the bird is still around, pausing at the feeder, giving you nice long looks through your binoculars. Yeah, it leans a bit raspberry, but the rest? When you compare it to the picture in your field guide, which will soon require an application of Wite-Out, you start to accept the inevitable—that slightly pink-looking finch turns out to be a less deeply-red colored version of the House variety, the one you’ve seen daily your whole damned life.

Time to revise that eBird checklist.

Things weren’t always this way in the eastern US. Historically we had Purple Finches, and we IDed them with confidence. We liked them. Loved them even. Hell, some live-free-or-die types loved the Purple Finch so much they made it their official state bird. But House Finches? To someone like me in Pittsburgh, PA, they were a mystery bird from a faraway land.

So how did we get here? How can it be that House Finches are everywhere, not just in Pittsburgh but the entire eastern part of the country, while Purple Finches are something most of us only hope to see when the weather turns cold? And what the hell is with the asterisk that appears next to House Finch on our eBird checklists?

To answer these questions, let’s take a trip back in time. The year is 1940, an inflection point in the history of our nation and of the world. Armies everywhere have laid down their weapons. Humans are united in the spirit of peace and fellowship. The American League’s Cleveland Canvasbacks are preparing to defend their 17th consecutive World Series title. Eleanor Roosevelt, in the third term of her presidency, has made universal healthcare the law of the land. And in Ryan, Oklahoma, Wilma and Ray Dee Norris have just given birth to one Carlos Ray “Chuck” Norris, whose series of nature documentaries will one day catapult him to fame as the top conservationist of his time, leading to the cessation of fossil fuel use worldwide and ultimately halting the march of climate change in its tracks…

Okay, you’ll forgive me for indulging in some fanciful license here. The truth is, 1940 was an inflection point, not just in geopolitical terms, but also in terms of medium-sized red finches. In 1940, pet stores in the New York metropolitan area were awaking to a very harsh reality. Efforts to market the western “Hollywood Finch” as the latest sensation in cage birds—likely facing insurmountable competition in more colorful and charismatic lories, parakeets, and cockatoos—were failing. Furthermore, trapping and caging these wild birds ran afoul of the Migratory Bird Bird Act of 1918, subjecting the offenders to possible criminal prosecution. Big risk, little reward.

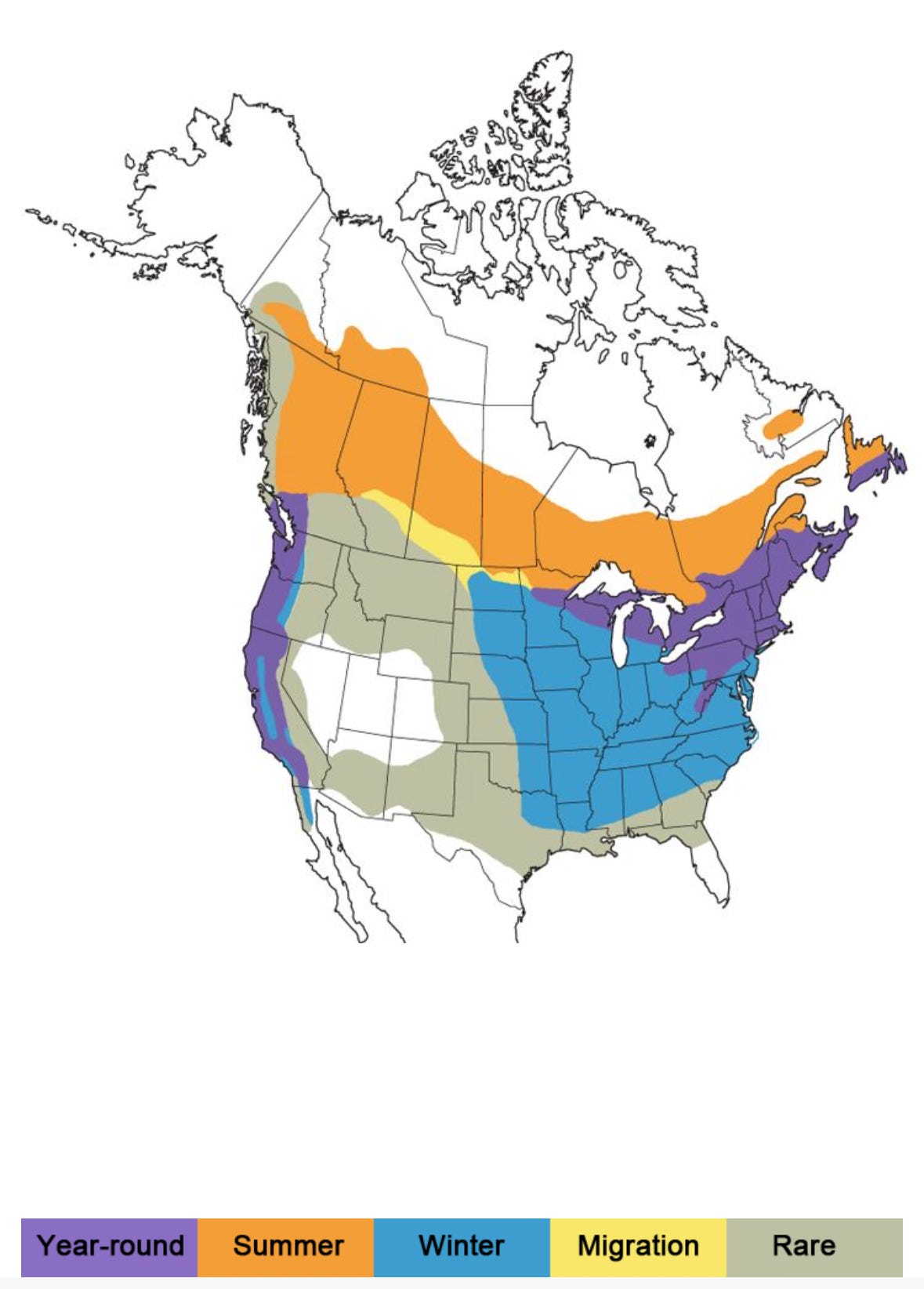

And what happened when, sometime in 1940 (or 1939, depending on whether you believe Cornell or the Audubon Society), a few captive Hollywood (AKA House) Finches were set free on Long Island? Well, there’s a reason why, some 85 years later, the bird’s range looks something like this.

House Finches proved a hardy, adaptable bird, and their spread from Long Island across the continent came fast and furious. And there’s the reason for your eBird asterisk—House Finches are not native to the eastern United States. Why they’re not treated with the same revulsion as House Sparrows and European Starlings is perhaps a bit mysterious, unless there’s some nationalist bias and inherent xenophobia in play and House Finches are offered a more charitable attitude by virtue of being invaders from within the continental US.

But invaders they were, and as House Finches were conquering all the lands unchecked in the subsequent decades, Purple Finches were busy being Purple Finches, though I suppose there must have been some confusion about the sudden appearance of a new, somewhat similar-looking finch, and more than some distress about how aggressive their western counterparts were proving when a food source was in play.

Whether the arrival of the House Finch has contributed to the more than 30% decline in Purple Finch populations since the 1960s, I can’t say for certain, though it seems likely that being outcompeted for resources has played at least a supporting role.

What I do know is what the birdwatchers of the east were in for as the number of stripey finches appeared with increasing frequency in cities, parks, neighborhoods— wherever humans had a presence. Take my hometown of Akron, Ohio, for example. According to Audubon Christmas Bird Count historical data, House Finches arrived for good in Northeast Ohio sometime in the 1970s, nearly 40 years after their release in Long Island.

Three House Finches were reported in the Akron CBC of 1978. In the nine subsequent years, the number rose astonishingly fast, peaking in 1987 at 2,192. The Purple Finch meanwhile was first reported in Akron’s CBC in 1945 with a tally of five. Due to disease and other factors, the House Finch population has fluctuated rather wildly in Akron CBCs, which is food for another post, but suffice to say that the 1987 level did not prove sustainable. In last year’s CBC, the House Finch/Purple Finch count stood at 187/1, respectively.

This has all been a meandering way of saying two finch species that look fairly alike now solidly overlap in range and thus present a challenge for eastern birders. I would know. I certainly talked myself into seeing a Purple Finch where there was none more than a handful of times, and it took years of dedicated yard birding before finally spotting a slam-dunk Purple Finch.

And I use the phrase “slam dunk” because… are the two species really that similar? Because I think another rite of passage for a beginning birder is to finally see a Purple Finch at the feeder and nod rather epiphanically, Ohhhhhhhhhhhh. Now I get it.

Let’s compare. I was lucky to see a mixed flock over Easter weekend at my brother’s house in Akron. For one day at least, House and Purple were willing to play nice.

Before diving into the differences, it must be acknowledged that there can be wide variation in the field marks of these birds. I’ve seen or heard of House Finches running from a deep crimson to pink, orange, and even yellow. And certainly a few individuals from a single morning of photography is a paltry sample size. Still, these specimens are good examples of the general differences between the birds. The distinct coloring of the male finches really jumps out here, not just the difference between the raspberry Purple Finch (left) and the rosy House Finch, but also the uniformity in coloring. The raspberry of the Purple Finch extends much further down the breast and back, but also into the wings and even the rump/tail, blending here and there with black and rich shades of brown. The House Finch’s red coloring is much more limited, with little or none in the back, wing and rump/tail. Also note the streaking on the flanks of the House Finch, absent or all but absent on the flanks of the male Purple Finch. The lack of red really puts into relief the, let’s face it, drabness of the House Finch’s grayish-brown.

As for the females—at a glance they may seem more difficult to tell apart, but again, upon closer inspection, are they really?

With the females, we obviously can’t rely on color to guide us in identification. We’re talking brown and white here. What’s striking is the more defined facial pattern on the female Purple Finch (left)—two white stripes that really pop. Note also the differences in streaking. The female House Finch sports a rather uniform pattern of streaks, while the streaks of the Purple Finch, composed of almost triangular spots, are laid out much more sparsely. The white belly of the female Purple finch is also largely free of markings.

There are some further distinctions I wouldn’t always trust with my eye—shape of head, length of tail, notch in tail, plumpness, etc. These differences are minute enough that I’ll defer to the Master of Minutiae, David Sibley, who lays it all out in exquisite detail as only he can. It’s also worth noting that shape and size can be maddeningly difficult to discern among birds in flight, flitting around feeders, or buffeted against the cold.

So why are Purple Finches, native eastern birds and willing visitors to our yards and feeders, somehow so elusive? For one thing, consider their year-round range, which is far more limited than the House Finch’s.

Purple Finches are also far less cozy around humans. For example, Purple Finches prefer to nest in trees, while House Finches will build nests just about any goddam where—a flower pot, a light standard, and yes, your house. House Finches can be particularly aggressive around food sources, outcompeting and possibly displacing native birds, including Purple Finches. Purple Finches are also irruptive migrants, meaning their presence in winter and how far out of their typical range they’re willing to travel depends largely on the availability of food. For me personally, this was a good winter for Purple Finches. I saw many of them in various locations around Pennsylvania and Ohio. Just this week I’ve seen flocks at feeders in suburban Akron and in the wooded parks of Pittsburgh. Some winters I see none at all. Put another way—House Finches are everywhere, all the time. Purple Finches? Not so much.

No doubt the sudden bounty of Purple Finches this week means they had a significant irruption south and are now headed back to their breeding range. We certainly wish them luck in spawning the next generation.

And speaking of next generation, what does the future hold for Purple and House Finches? Can the species coexist in the decades to come? Will House Finch populations overcome disease and continue to increase, leaving little to no room for competing species? I hope not, and I suspect not. Purple Finches may get bullied away from feeders and human populations in general, but hopefully they’ll find refuge in the forests, away from humans, away from the lookalikes that spawned from that fateful day in 1940. The birder in me hopes it never comes to that. I love an ID challenge, and I hope birders can prowl their feeders in Purple Finch anticipation now and forevermore.

Featured Photo—Female and Male Purple Finch

I don’t have much to add at this point, except this—aren’t they just so goddam beautiful?

10/10 Recommends

Changing the Name (and not Changing the Name)

When Roger Tory Peterson described the male Purple Finch as “dipped in raspberry juice,” he couldn’t have been more right. I don’t think it will ever happen, and I may be on a soapbox preaching to an audience of none, but I love when common names are not only descriptive, but also accurately descriptive. “Purple” Finch may be sorta accurate, but purple is a bit generic. There are shades of purple, and raspberry strikes me as a perfect representation of the vibrant color on a male Purple Finch. And Raspberry Finch is a far more poetic name than Purple, in my opinion.

As for House Finch? Perfect name. Never change it.

That’s all for this week. Have you had a similar experience confusing Purple Finches and House Finches? Are Purple Finches plentiful or scarce where you live? Why do you think House Finches are treated more charitably than other invasives? Tell me all about it in the comments!👇

Until next time, bird your rassberry off!

nwb

Enjoy this post? Birding with BillBow’s weekly content will always be free, but you can help support my writerly dreams in the form of a paid subscription (save $10/year by choosing the yearly plan!).

Or buy me a beer. No better way to celebrate a hot migration day than with an ice cold beer.

Paid or not, thank you for reading! I’m so glad you’re here!

This post was human generated. All photos by Nathaniel Bowler except where noted.

Great piece. Really informative writing, Nate, and fun to read.

I embrace Occam's Razor when I bird, when I see a finch I have to prove to myself that it's not a House Finch. There's are Purple Finches where I bird, but when a bird reveals itself to be a Purple rather than a House Finch it's a treat. As you say, they feel elusive. It's also a chance to flex some birding knowledge to myself and show that all this birding has yielded some know-how.

As for being treated charitably, I think part of it has to do with House Finches being pretty. Starlings and House Sparrows are pretty, but House Finches are more objectively pretty, I think.

I am excited about your Substack. I came across it by accident. As I am a new birder ( this last fall I became interested-a story I tell on my Substack) I am looking forward

To learning by reading your posts.